When it comes to storytelling, no matter fiction, film, or theater, it all comes back to Shakespeare. From required reading in high school and college to reinterpretations and modernizations, the Bard is always number one.

In last month’s column, I mentioned two movies, The Abominable Dr. Phibes and Dr. Phibes Rises Again, starring horror icon Vincent Price. Each of these two revenge movies are stylish but campy British film productions that capture the lurid side of the ‘70s. But the weird thing about these films is that Price, who plays a horribly scarred organist and theologian, is mute. This detail robs Price of his greatest weapon: that booming voice. Just ask any kid who remembers Michael Jackson’s Thriller album and they’ll tell you.

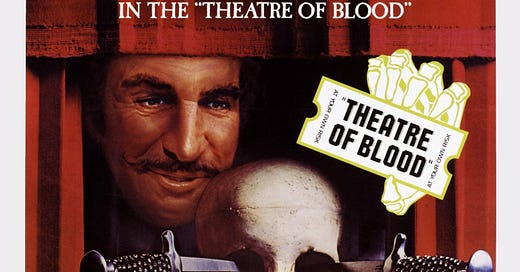

So when Price was choosing his next film, he stuck to the formula of killing perceived enemies one by one. But after two movies of having no dialogue, he picked a script that gave him the meatiest of all words: Shakespeare’s greatest monologues.

Theater of Blood features Price as Edward Lionheart, a hammy Shakespearean actor who, at the beginning of the film, is believed to be dead. When theater critic George Maxwell (Michael Hordern) is summoned by the police to a dilapidated housing project which he is in charge of razing, he is attacked by a group of homeless people. The bobbies appear to condone their behavior, revealing Edward dressed in police blues. As this day is the Ides of March, Price drops into Mark Antony’s eulogy of Julius Caeser as the critic gets repeatedly stabbed.

Thus, the film sets its theme. A critic gets drawn away to an isolated location, usually a dilapidated theater where Lionheart and his minions live, because they get their ego stroked in one way or another, then they die in a theatrical way. A few of the deaths go off script. The Merchant of Venice, which features no deaths, gets its pound of flesh regardless and a sword duel in the style of Romeo and Juliet becomes an intimidation instead of a murder.

While Lionheart continues his reign of terror, head of the critic’s circle Peregrine Devlin (Ian Hendry, The Avengers (TV), Get Carter) tries to get help from Lionheart’s daughter Edwina (Diana Rigg). Head Investigator Boot (Milo O’Shea) tries to keep the remaining critics safe, but they keep running off by themselves and into Edward’s waiting traps.

Spoiler Alert for this paragraph: Riggs does some very interesting work in the film. Falling in between her celebrated TV work on The Avengers and her later roles on BBC, she plays a very convincing mourning daughter while also being the lead player in her father’s traps. Once she sports a blonde wig and white miniskirt and go-go boots, but mostly in male drag as a curly-haired, walrus-mustachioed hippie with a Cockney accent. It must have been great fun for her playing against both the screen legend Price and her old co-star Hendry.

Director Robert Fuest was tagged to do this film because of his Phibes work, but he refused, not wanting to be stereotyped as a Price-only director. Douglas Hickox took over the reigns and brought a great deal of style. This film is full of ironic match cuts (edits which comment on the previous shot), inventive forced perspectives which create extremely interesting frames, and creative angles: low, high, bird’s eye, anything which gives some oomph to the shot. He didn’t have many celebrated films, but this one is a masterwork of both comedy and horror.

What adds to Hickox’s flourishes is the fun that all the English character actors adding their own camp to the critics. Robert Morley, Harry Andrews, Jack Hawkins, Robert Coote and Coral Browne all mince and tiptoe and twiddle fingers through their hammy sides. Screenwriter Anthony Greville-Bell adds to the fun by slyly naming these critics: Peregrine (as in the raptor), Dickman, Larding, Sprout, Psaltery (say it out loud), and the least hidden, Snipe.

But it all belongs to Price. He adds mustard to his already hammy way by adding increasingly crazy stage makeup, crazier set pieces, and wonderfully flourished delivery of the Bard’s words. He doesn’t run from the assignment but grabs it with both hands, delivering a self-aware actor’s actor performance which also gives Shakespeare the spotlight through his great instrument.